Death by inflation

Most Britons lose when inflation hits and prices soar. Inflation could rise significantly in the UK. What does that mean for ordinary Britons and why does inflation kill an economy?

I read an interesting article the other day that outlined how France – despite 138% debt to GDP and nearly 6% pa deficit – is paying less to borrow than the UK. The UK technically remains below 100% debt to GDP and only about 4.8% deficit (although both those figures could probably be taken with a pinch of salt as things stand).

What really differentiates the two, though, is bondholders’ views on inflation. And there the difference is very much in France’s favour. Taking the 10 year bond yield, France’s at the moment suggests 2.7% as opposed to nearly 5% for the UK. Not to put too fine a point on it, but that means the expectation is that UK inflation will outpace France’s by around 2.5% or nearly 100%. And if there’s one thing bondholders hate it is inflation – unlike Governments who love it. In case you don’t know that is because Governments borrow today and pay back multiple years later.

But what does that mean for the UK? Of course, it means we will have to pay more to borrow for a start, but what will be the effects on the ground?

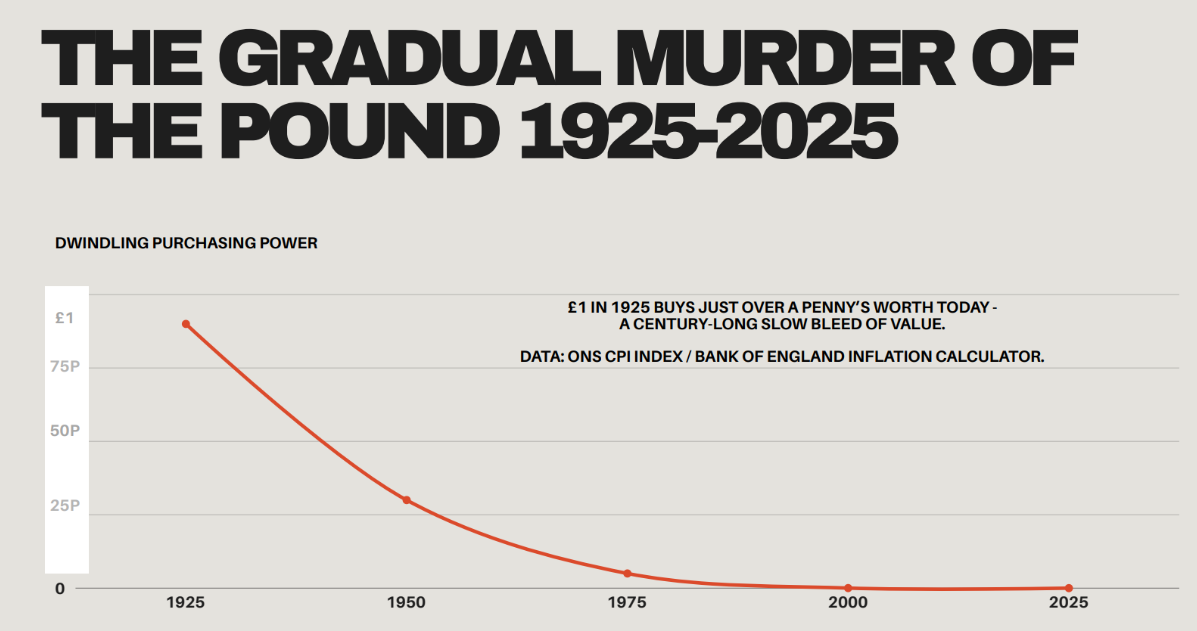

Before looking at that, we must discuss how inflation has effectively destroyed the value of all currencies over the last 100 years, so much so that £1 in 1925 would need more than £77 now to buy (give or take) the same basket of goods. So if the Government borrowed £1 in 1925, it would have the present-day value and use of that money in 1925. When it came to pay it back in 2025, it would pay – wait for it - £1. Not £77. From a Government point of view, what’s not to love?

The pound had an average inflation rate of 4.45% per year between 1925 and today, producing a cumulative price increase of 7,669.23%. That means just to keep the value of your asset the same, you would have had to earn 4.45% interest every year, not to make anything, just to not lose anything. And what with tax and one thing and another, you would probably need about 6% as a minimum to stand still.

Economics 101 (an expression I hate) tells you that if the money supply grows faster than real production of goods and services, your purchasing power always drops. Wage settlements above inflation, drops in productivity, and increasing taxes – all result in higher inflation and less to go round. What THAT means is we have increased the money supply by that average each and every year. It’s a simple calculation. Increase the money supply by 5%, [prices will rise by a similar amount.

The best example of how to manage monetary and economic growth remains the German Wirschaftswunder of the postwar era up to about 1973. Ludwig Erhard, the German Economics Minister for much of this time, basically stated the fact that excess money leads to excess demand and hence increasing prices. So he set about making life as simple and stable as possible for businesses and giving them certainty. He increased the money supply by 2% per annum for years. Never more, never less, but held absolutely steady. What that meant was that business KNEW what was going to happen. There was no tinkering at the edges. It is true that the Reichsmark was replaced by the Deutschmark in the early stages, which instantly stopped inflation in its tracks, but at the same time, the tax rates on ordinary citizens were slashed. Whereas previously 95% was the rate levied on people earning more than DM6000 (about £535 then or £23,000 now. In case you aren’t paying attention, that’s what inflation does. It operates like a tax on earnings, taking money from individuals so that their standard of living is reduced.) More importantly, the tax rate fell to around 18% which meant there was much more cash available to be spent to support businesses.

But Erhard went further. Largely against most special interest blocks and even his own advisers, he abolished price controls. He did it on a Sunday so that the Allied powers, who were still controlling Germany, wouldn’t know until too late on the Monday. Up to that point, food had been scarce, and the black market reigned supreme. What happened almost immediately was that the shortages disappeared. The economy improved dramatically. Supply and demand were able once again to find their own levels, and the price mechanism could work. Once goods could be sold for a price that reflected the true cost of production, to no one’s surprise, production increased. The economy naturally improved. It’s obvious, really. Tell someone you can only sell an apple for £1 when the market will bear £2, and the apples will be hoarded. Say you CAN sell it at £,2 and suddenly you have apples coming out of your ears.

One of the stories I like about this era is about a previously well-off lady who had picked up some flowers and brought them into the town. Before she even got home, she had people asking to buy them. She didn’t sell them, but the next day she took a bag and picked up a whole lot of flowers and was again accosted as she made her way home. This time of course, she sold them and had none left. And so it went – she got a barrow. She got a helper. She started a shop. Anyway, within a few years, she had a massive flower business right across Germany. But the real point here is that flowers were not subject to price controls, and so she could charge what she liked. People wanted a bit of cheer. So they paid. As an aside, during the war, apples, for example, had a controlled price. So in the wholesale markets, you might have been selling a box of apples for say £2. The shopkeeper would package up each apple with other foodstuffs that were NOT controlled and sell that box of apples which should have been say £10 retail for £20. And in the market, if you wanted to buy that box, you had to buy, for example, cabbage. So the £2 box became £5 because you had to buy 10 bags of cabbage. You probably didn’t bother to collect the cabbage, so at the end of each day, you would find that instead of 100 bags of cabbage left, you would have 500. Which you wrote back to 100 with “wastage.”

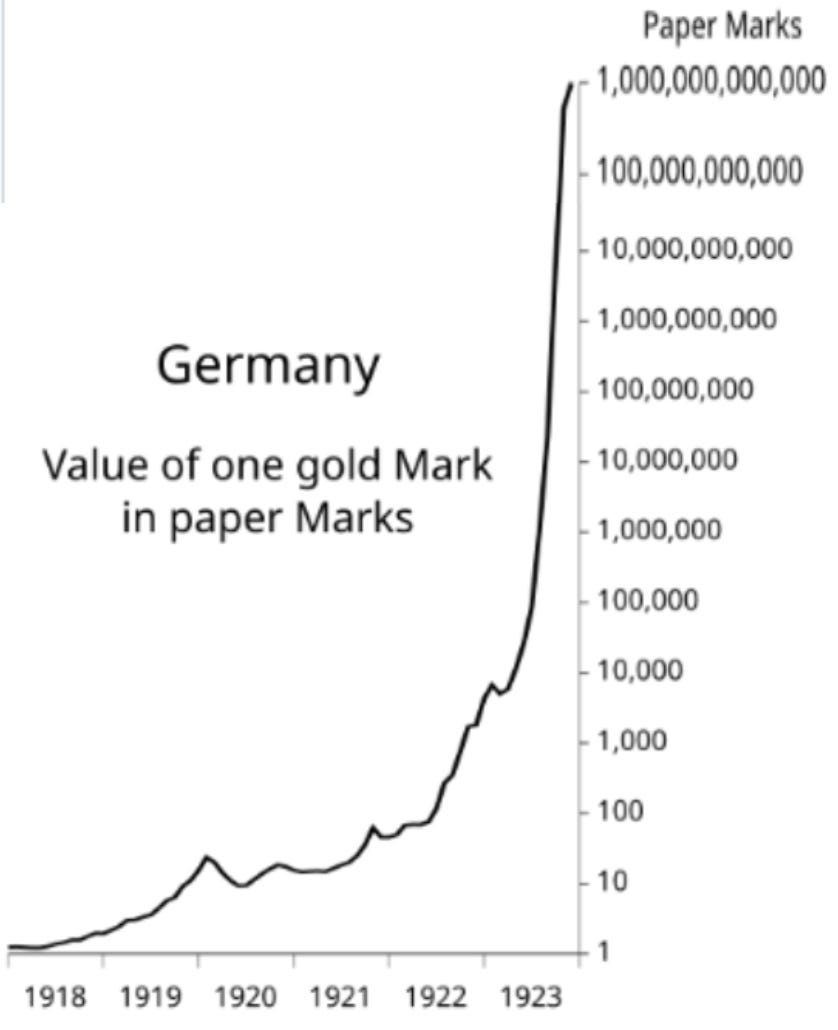

And what of the 2% monetary boost every year, boringly churning away? 2% is enough to make it possible to have a decent interest rate above the rate of inflation – just ask South American countries how to do that. Hasn’t happened in decades. That has a beneficial effect on the velocity of money in the system and everyone can get rich. You may remember that the Deutschmark was revalued several times in the 1960s and 1970s, effectively reducing import prices for German consumers. Going back further, the Weimar Republic seared the German conscience as a loaf of bread that cost around 160 Reichsmarks at the end of 1922 cost 200 billion marks by late 1923. By November 1923, one US dollar was worth 4.2105 trillion German marks. That is what continuing to print money does to its value.

So who are the winners and losers from inflation?

Losers:

People on fixed incomes: Retirees and others who receive fixed payments (like Social Security) lose purchasing power as their income doesn’t keep pace with rising prices. One of the reasons we have the “Triple Lock” for pensioners.

Cash savers: Individuals with money in savings accounts with low interest rates see the real value of their savings decline, as the interest earned does not keep up with inflation. Practically everyone with any cash has lost ground over the last few years

Workers with little bargaining power: Those in low-paying jobs with little to no union protection may see their wages stagnate while prices rise, leading to a loss of purchasing power.

Lenders (potentially): If the interest rate on a loan is lower than the inflation rate (negative real interest rates), the money the lender receives back is worth less than the money they originally loaned out.

Winners:

Borrowers with fixed-rate debt: The real value of their debt decreases over time (as I’ve already mentioned in relation to Governments) as they repay loans with money that is worth less than the money they originally borrowed.

Producers and businesses: Companies can benefit if they can raise prices on their goods and services faster than their costs increase, leading to higher profit margins. There is, however, always the constraint of customer resistance to higher prices.

Real estate investors: Property values and rents can increase with inflation, making it a popular hedge against rising prices.

Workers with strong bargaining power: Individuals who can successfully negotiate higher wages to keep up with or exceed the rate of inflation can maintain their purchasing power. Train drivers, Junior doctors….

Investors with certain assets: Assets that are expected to rise with inflation, such as stocks, commodities, or certain types of real estate, can potentially provide returns that outpace inflation.

All that said, the general population is an overall loser from inflation, and as you can see, it’s only special interest groups that can benefit.

In 1920s Germany, there was a large “rentier” sector. Despite the bricks and mortar still being there, the hyper-inflation literally destroyed an entire important and erstwhile wealthy class. This alone might have contributed to the rise of Nazism.

You can see why monetary institutions try to hold inflation at 2-2.5%. What you don’t want is those institutions saying inflation created by massive quantitative easing is “merely a blip”. That cycle peaked around 11.1%. At that rate, £100 becomes worth only around £50 in a little over 7 years. Read it and weep.

Temple Melville is the Director of The Scotcoin Project and writes on crypto and economics for various publications, including The Digital Commonwealth and CityAM.

Thanks Brian. Appreciate the comment

Great informative piece. Hyper inflation was clearly a specific case to the then German economy. Just printing money is not the answer when an economy hits the buffers.

But as you pointed out the 2% increase in money supply to balance inflation of a similar amount balances out the scales.

I think what’s missing in all this is the value of money itself.

For my penny worth, no pun intended, money should be a fair exchange of work. A token of fairness and something to exchange in the same time frame. Your assessment shows the need for time to be considered.

But our present system does not do us justice in our modern economy.

It’s neither a fair exchange of work nor is it exchanged at all!

For example, was David Beckham worth a million pounds a month? That’s equivalent to 100 nurses. Is that a fair exchange of work?

David could earn this amount in our framework. Albeit unfair. But worse is that he can live at the same cost as a nurse. So in effect doesn’t exchange his money at all!

And now, because he didn’t spend his money in full, he can now loan it back to us instead of exchanging it. Still holding onto it. So as I say money is NOT fairly exchanged all of the time.

Another observation of now to the then if post war Germany of the 20’s is that they didn’t have digital banking! In those days they didn’t know who had money, where it was nor in what amount.

But today, that is all easy to establish. But only if money stays in house in the Country of origin.

For us, Thatcher stupidly took away exchange control regs in the late 70’s and now thanks to Brexit we can reinstate those rules.

It allowed our money to flow out and foreign ownership of our infrastructure. This was not clever it has led to our debt ridden position now.

Now, I’m not a communist. I’m all for earning as much as you can. I’m all for David Beckham earning his money. If 50,000 people want to pay their money just to see him kick a ball then, who am I to say no. In fact it’s our right to earn and spend on what we want. We have all earned that right by fair gain and fair exchange.

But unless those who get paid in turn, also spend their money, how can the cycle of fair exchange keep perpetuating? It can’t at present.

Our system allows money to be held unspent, unused and idle. In fact hoarded.

The effect of this is making us all devoid of that money, it underfunds our economy and underpays tax. And when we get low on money we borrow it from the same people who are allowed to hoard it.

All because our money system is as old as the hills. It’s the same system that led to the German hyper inflation. When money becomes worthless because a fair exchange of work doesn’t get rewarded. And the wealthy are those sitting in real asset property gold etc.

So how do we get it right?

I say, reinstate exchange controls. Swap all money digital and cash for a new digital currency.

Put a ‘spend by date’ on all that new money. Make it move constantly. In fair exchange of work.

Spend it or lose it to the exchequer. Make wealth be what asset and goods you buy with the money.

But instantly the money supply is finally assured to give us the money and spending and the tsunami of cash flow we finally need. Autonomous and perpetual flow of free unencumbered money.

Goods can flow. But not money.

Make other countries hold uk accounts to buy and sell goods in the same way. So they have to spend it lose.

Wages will rise above the low level of benefits. Finally showing work pays. Not like now underpaying workers because of insufficient money supply from hoarding money.

Better state pensions avoiding the need to have a second pension.

And ironically the rich will be wealthier. From all that increased extra spending!

No more borrowing no more government debt.

That’s a better system and modern.