Rachel Reeves first major misstep

If the Chancellor tells us the UK can't afford public spending, she is right. The Conservatives should use the opportunity to promote lasting change, better to serve the public and avoid disaster.

Rachel Reeves, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, is expected on Monday to give a statement on public spending “pressures” amounting to tens of billions of pounds. It is not credible to suggest this will be a surprise, as Paul Johnson of the IFS explained on the Today programme this morning (07:37).

Either it will be a restatement of what is already known – in which case any claim this is a surprise is frankly dishonest - or it will be a wish list of spending which government departments would really like and may have bid for in spending reviews – in which case elements will range from the unaffordable to the fanciful. Reeves is not at all likely to raise taxes on Monday but instead to set the scene for rises later.

It is Rachel Reeves first major misstep. Not because the Labour party promised not to raise taxes on working people: this early in the parliament, as politicians so often do (alas), they may simply break their promises, blaming their predecessors.

It is a major misstep because with taxes at historic highs, and likely at or beyond Britain’s taxable capacity, Reeves would be telling us an unspoken truth which undermines her party’s faith in big government: that the UK cannot afford the state we have. She would be right and the Conservatives should point that out.

Atlas is shrugging: the public cannot afford the burden of the state placed upon them and on which so many are dependent: not now and not into the future. A time for choosing is fast approaching, probably at the next general election, once Labour have further tested the limits of their ideology of the big, entrepreneurial state.

With more people living longer and so many people dependent on the state for pensions and healthcare, the UK faces an exceptionally serious problem which must be solved. It is repeated elsewhere.

The situation

Throughout my time in parliament, I explained politicians have long been selling cruel fairy tales of unaffordable benefits. Cruel because so many people rely on promises which ultimately cannot be kept and, in so far as they have been kept over my lifetime, that has arguably been through methods which insidiously manufacture injustice in ways which are barely understood.

These problems are now crystallising and seem set to work themselves out dramatically and continuously over the next 20 years and beyond.

Spending

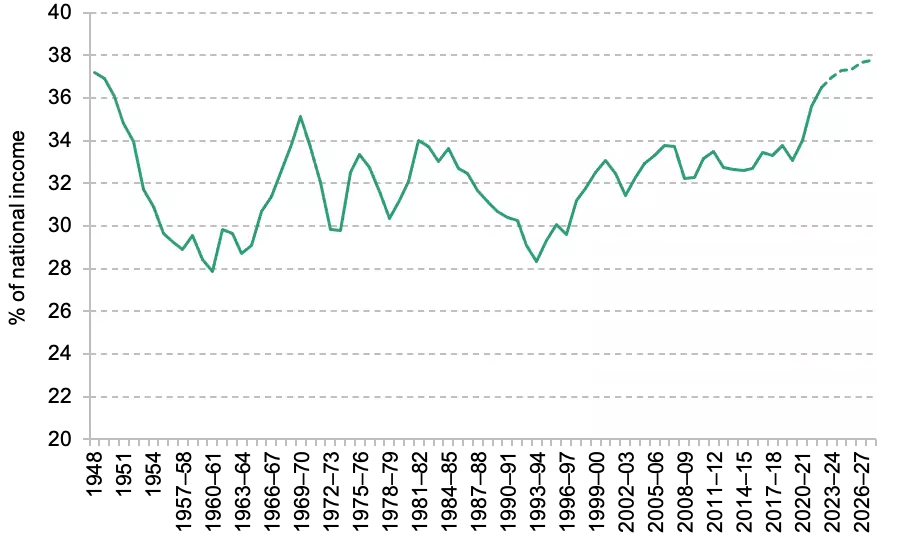

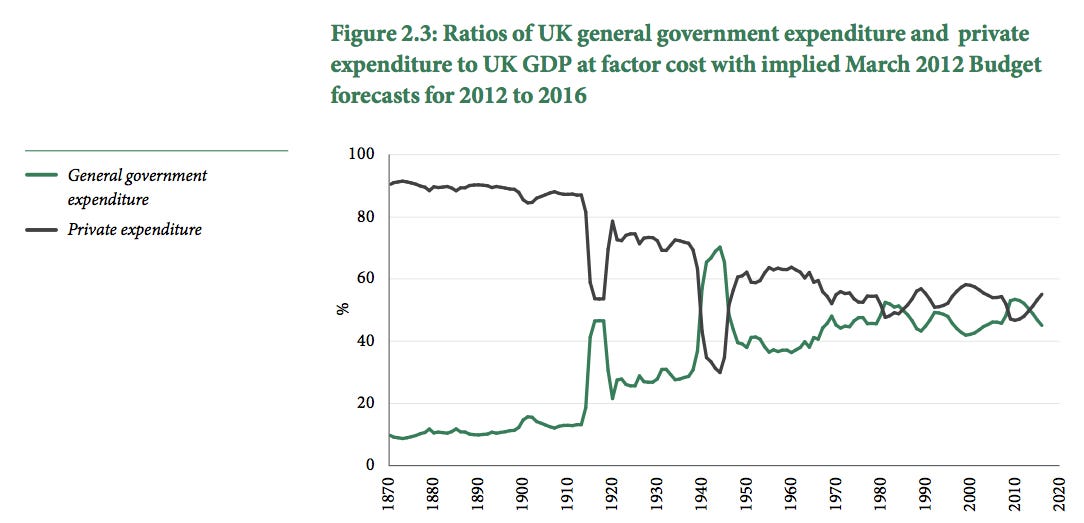

We have not had limited government, low taxes, balanced budgets (with brief exceptions) and sound money since before the First World War. Check the report of the 2020 Tax Commission for details. Here is the chart on expenditure:

Prior to the First World War, the dominant political ideology – the centre ground – was classical liberalism, however imperfectly applied. After two world wars, the dominant ideology everywhere was a kind of managerialism or social democracy: a belief in the omnipotence of state power to improve our lives.

The period of transformation from one centre ground to another generated an immense literature as intellectual leaders worked out what on earth had created such catastrophic human suffering. If I were to recommend one book1, it would be The Managerial Revolution: What is Happening in the World by reformed American Trotskyite2 James Burnham. He argued capitalism was dead, replaced everywhere not by socialism, but by managerialism: the rule of administrators in government and in business.

This doctrine of managerialism continues to fail: that failure is becoming increasingly difficult to cover up.

Since time immemorial, rulers have funded their governments in three ways: taxation, borrowing and currency debasement.

Taxation

As the IFS explains, taxes are today at “a level not sustained in the post-war period”:

The economist David B Smith was kind enough to write a paper for the Treasury Select Committee at my invitation titled, What is the Upper Limit to Britain’s Taxable Capacity? It was subsequently expanded to a paper for Politeia.

He found evidence for practical limits to taxation. He also found that, even before Covid-19, UK general government spending was stuck at about the limits of taxation, non-tax receipts plus 3% borrowing. That level has often triggered crises in the past.

It is extremely difficult to believe Rachel Reeves can raise taxes from this position without doing immense harm to the economy and taking terrific risks.

Borrowing

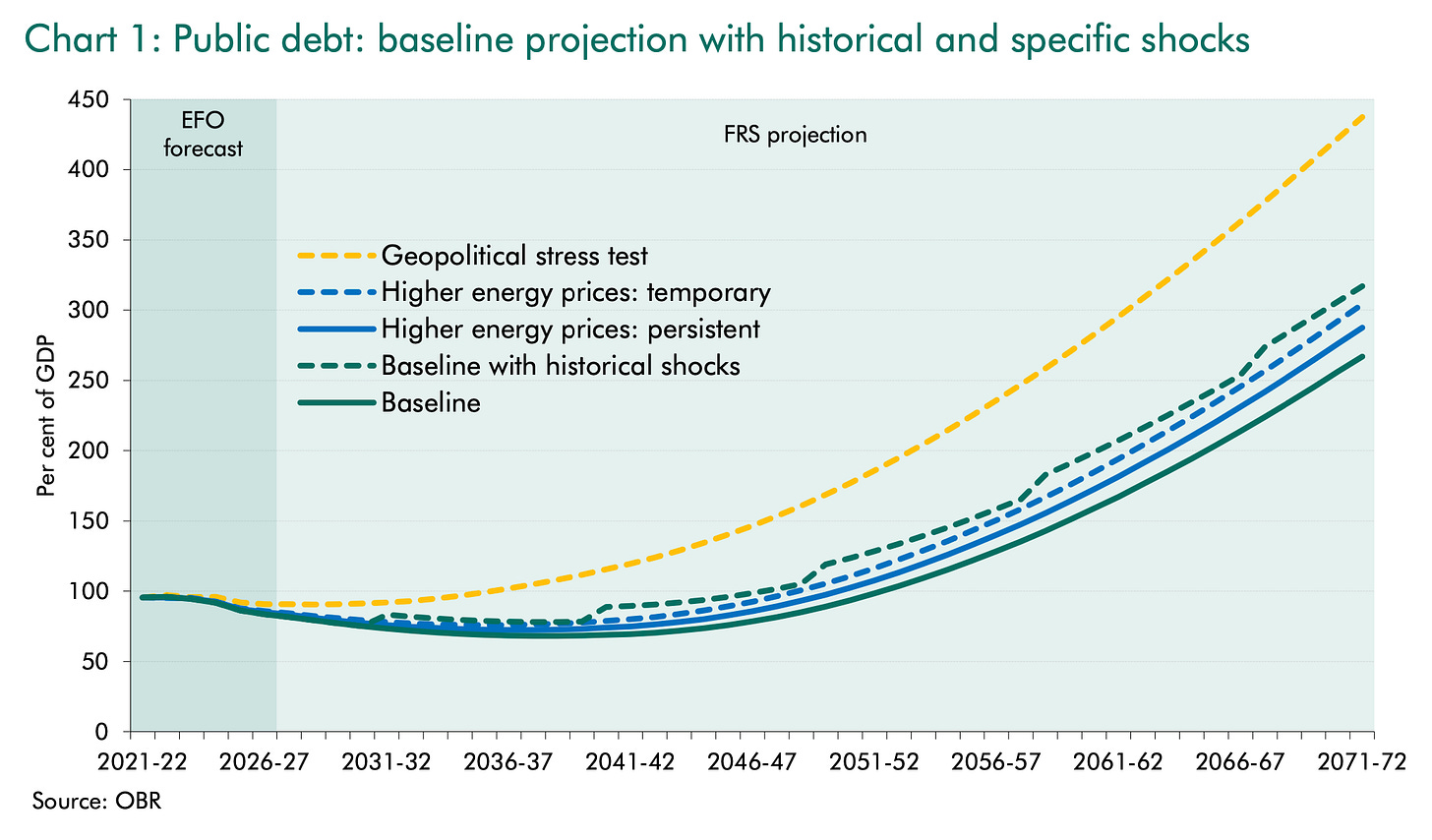

Every two years, the Office for Budget Responsibility produces a fiscal risks and sustainability report. This year’s is overdue thanks to the election, so for now we rely on the 2022 report.

They write:

Our long-term projections show debt rising to over 100 per cent of GDP by 2052-53 and reaching 267 per cent of GDP in 50 years if upward pressures on health, pensions and social care spending, and the loss of motoring taxes, are accommodated (Chart 1). Bringing debt back to 75 per cent of GDP – the level at which it stabilised in the Government’s pre-pandemic March 2020 Budget – would need taxes to rise, spending to fall, or a combination of both, amounting to a 1.5 per cent of GDP additional tightening (£37 billion a year in today’s terms) at the beginning of each decade over the next 50 years.

In 2018, the OBR was more explicit:

Needless to say, in practice policy would need to change long before this date to prevent this outcome.

In other words, age-related spending would have to be cut dramatically3.

It gets worse.

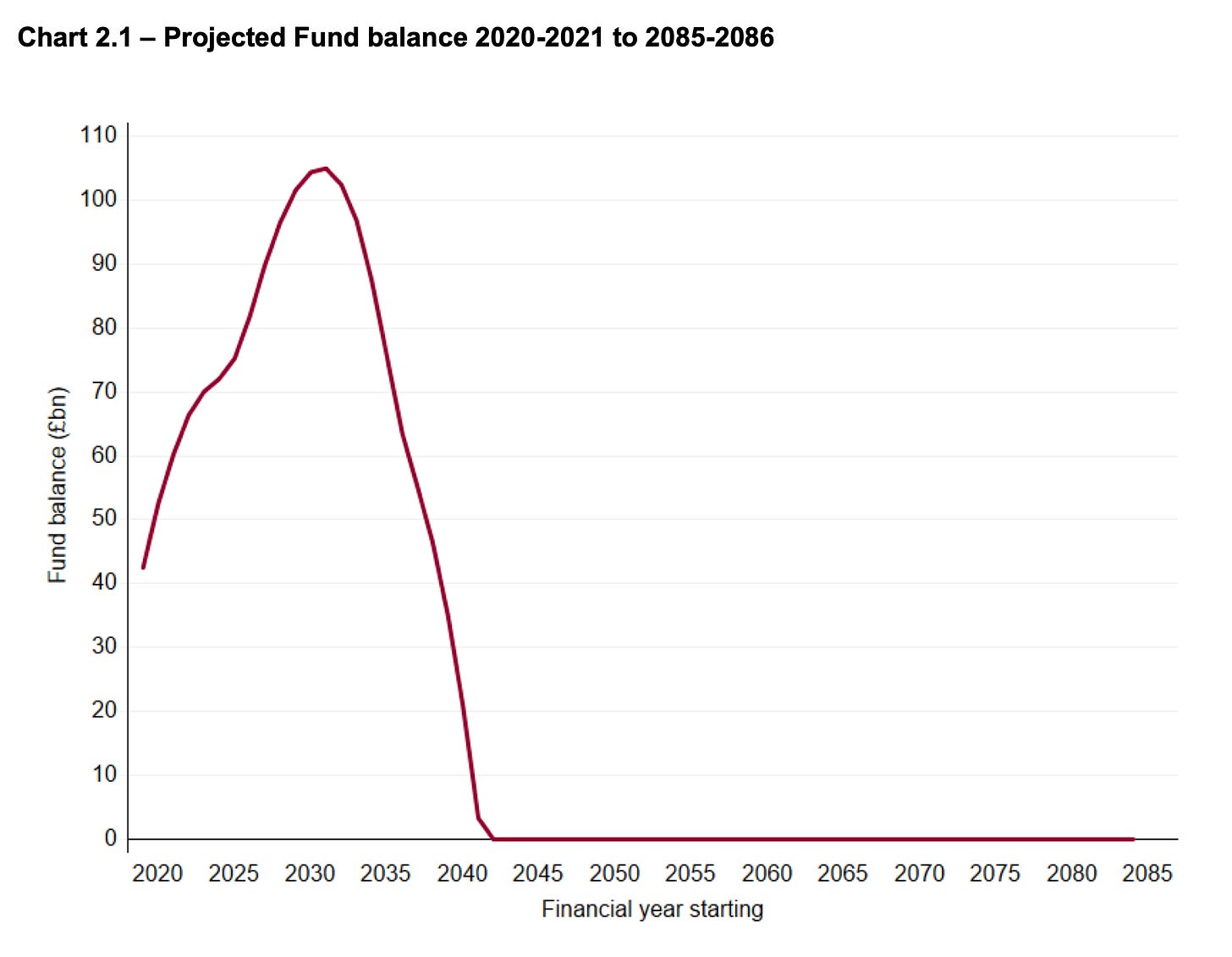

The National Insurance Fund is not where everyone’s National Insurance Contributions go to earn a return to fund later benefits. Alas no. Somewhat like your current account, tax revenue comes in and benefits go out. The balance must remain above zero. The Government Actuaries keep an eye on it.

The Quinquennial Review of the National Insurance Fund as at April 2020 looked at the extent to which the Fund may be able to support demand for benefit payments – unemployment benefits, sickness benefits, retirement pensions etc – over the period of 2020-2021 to 2085-2086. The Fund is forecast to reach zero in 2043-2044.

The review states in paragraph 1.2:

The principal projection to 2085-2086 shows that the Fund balance is projected to rise to £104.9bn in 2032-2033 then to decrease and, in the absence of any additional financing, will be exhausted in 2043-2044. This projection does not allow for any Treasury Grants that may be paid in the future to support projected benefit expenditure.

Given the remarks on tax above, it is a bold assumption to think this additional financing will be forthcoming.

In effect, this means that the UK is on course to default on welfare spending commitments in 2043-2044.

Those 20 years are four parliaments: the imperative for change is acute if the state is to provide for people who cannot provide for themselves in the years ahead.

Currency debasement

When money was gold and silver coins, rulers would recall them, clip the edge and mint them again, diluted with cheaper materials like tin. Today’s system of expanding the money supply is more subtle but it still supports larger government spending.

Governments borrow by issuing bonds. These may be indirectly bought by the Bank of England or by commercial banks: in either case, increasing the money supply smoothes the process.

It seems today fairly widely understood that the Bank of England creates money through Quantitative Easing. Less well understood is that in the modern economy, most money is ordinarily created when banks lend.

Over the years, I have found this is widely disbelieved, not only by members of the public – who think banks lend savings – but also in my experience by professional economists and people working in the financial system. It is extraordinary.

The Bank of England explains in the brief paper Money creation in the modern economy:

This article explains how the majority of money in the modern economy is created by commercial banks making loans.

Money creation in practice differs from some popular misconceptions — banks do not act simply as intermediaries, lending out deposits that savers place with them, and nor do they ‘multiply up’ central bank money to create new loans and deposits.

The amount of money created in the economy ultimately depends on the monetary policy of the central bank. In normal times, this is carried out by setting interest rates. The central bank can also affect the amount of money directly through purchasing assets or ‘quantitative easing’.

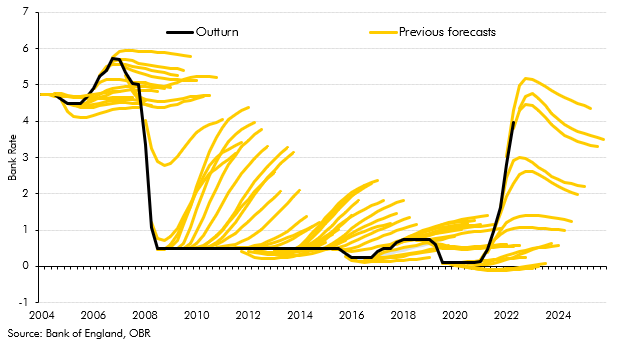

Here is the recent policy of the Bank of England:

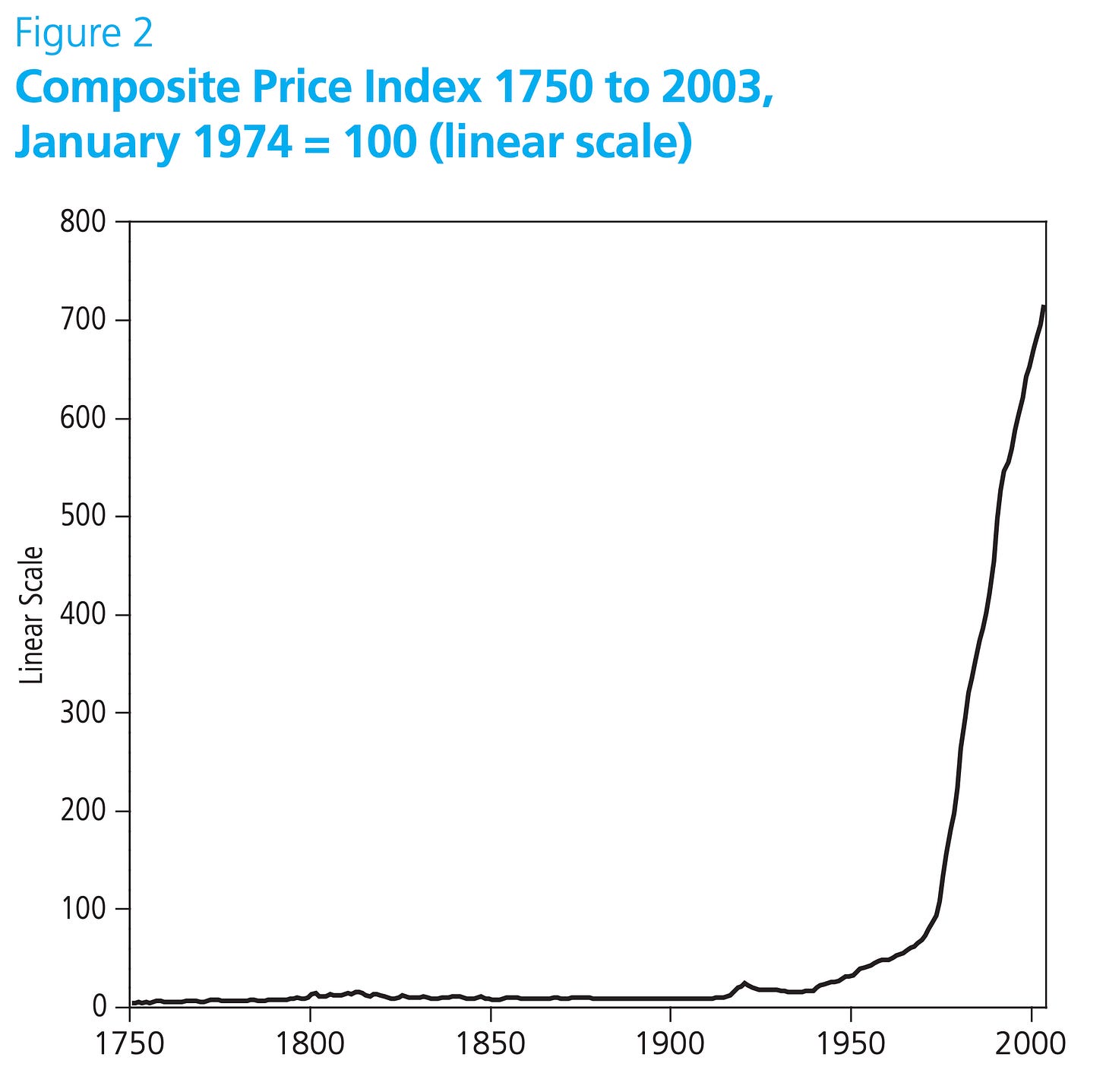

There is a vast amount to be said about the monetary system, far beyond the scope of this article. However, the consequence of the monetary system which has endured since 1971, when the last link between money and gold was severed was well illustrated in a paper by the Office for National Statistics and House of Commons Library, Consumer Price Inflation since 1750:

From the paper:

This article presents a composite price index covering the period since 1750 which can be used for analysis of consumer price inflation, or the purchasing power of the pound, over long periods of time. […] It shows that:

between 1750 and 2003, prices rose by around 140 times

most of the increase in prices has occurred since the Second World War: between 1750 and 1938, a period spanning nearly two centuries, prices rose by a little over three times; since then they have increased more than forty-fold.

Put another way, the index shows that one decimal penny in 1750 would have had greater purchasing power than one pound in 2003.

The value of money has been collapsing in our lifetimes, notably in relation to house prices: if you are young and wish to own a home, the injustice will be palpable, for others perhaps more insidious.

The famous economist Keynes knew currency debasement manufactured injustice. He wrote4, (emphasis mine):

Lenin is said to have declared that the best way to destroy the capitalist system was to debauch the currency. By a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method they not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some. The sight of this arbitrary rearrangement of riches strikes not only at security, but at confidence in the equity of the existing distribution of wealth. Those to whom the system brings windfalls, beyond their deserts and even beyond their expectations or desires, become ‘profiteers,’ who are the object of the hatred of the bourgeoisie, whom the inflationism has impoverished, not less than of the proletariat. As the inflation proceeds and the real value of the currency fluctuates wildly from month to month, all permanent relations between debtors and creditors, which form the ultimate foundation of capitalism, become so utterly disordered as to be almost meaningless; and the process of wealth-getting degenerates into a gamble and a lottery.

Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.

Hopefully, questions arise in the reader’s mind about the potential causes of the many social, economic and political difficulties now afflicting the world. It is a subject to which I will return.

Conclusion

The evidence suggests that we cannot afford the state we have, not now and not in our lifetimes. Taxes are at historic highs and it is implausible to believe they can be raised usefully. Debt is heading into unsustainable territory and the National Insurance Fund will be exhausted in 20 years, putting a date on the currently inevitable default of the welfare state.

Moreover, the evidence is that currencies have been dramatically debased since 1971, manufacturing injustice on a vast scale in ways which are rarely and poorly understood, but which appear to be reflected in commonly-expressed grievances which have been leading to political radicalism.

The situation facing the UK and the world is extremely serious. When Rachel Reeves on Monday tells the Commons we cannot afford present spending, the Conservatives should make the most of it in the public interest.

Perhaps the Chancellor means to cut spending, cut taxes and go for the growth we need but it seems unlikely. More probably, Rachel Reeves is more correct than she realises: as a former Bank of England economist, she is without excuse.

Further Reading

Are We In The Largest Bubble in History? – An Austrian School Analysis by Steve Baker MP & Max Rangeley (Yes, yes we are.)

Rethinking Economics, a reading list: www.stevebaker.info

Economics Primer, a reading list: www.stevebaker.info

My maiden speech in the House of Commons: www.cobdencentre.org

A documentary by the Cobden Centre on these issues: YouTube

Further book recommendations on classical liberalism are available on my website.

On 4 July 2011, I had an entertaining exchange with John McDonnell MP about Burnham’s book: he confessed he was “not completely reformed” (Hansard). He was subsequently very nearly Chancellor.

Since I relied on this at Treasury Select Committee, the OBR has been more circumspect, alas.

As far as I can discover, Keynes had no basis on which to ascribe the sentiment to Lenin but the passage illustrates that Keynes held the view, one elaborated elsewhere, that expanding the money supply creates insidious injustice.

I think chart 2.1 needs more explanation.

At first sight it seems astonishing that our NI reserves picture turns from one that is increasing from £42bn to £105bn between 2020 to 2030 only to then almost instantaneously reverse from £105bn to £0bn between 2030 to 2042.

The annual increase and decrease rates of £6.3bn and £8.8bn are probably not alarming based on the amount of NI collected each year (I do not know the figures but I guess that a typical employee has a joint employee/employer NI contribution of £3k and there may be 25m of them in the population creating a new NI fund of £75bn each year. Most of which is instantaneously spent.)

A spike in 2030 might be understandable if we had a birth spike in 1962, which I am not aware of, but if the steady state NI collection is £75bn per year then we only need to up it to £83.8bn per year to flatten the graph. I realise that this is asking working people to chip in an extra £350 per year but I would expect this Labour administration to demand that pensioners no longer pay no NI in retirement but continue to pay NI because “it pays for the NHS which you still use but now to a disproportionate effect”.

But I am still intrigued as to why there is an almost instantaneous rate change of £15bn per year in around 2030.

Steve, thankyou for your article. Very little divides us philosophically and the James Burnham book you recommend is such an important book, especially as it influenced Orwell's writing.

Having said that, it feels there is a subject I have not heard you cover. Perhaps 12 months ago I asked a parliamentary colleague of yours at a Question and Answer session what can be done about "The Blob". He seemed to not recognise the point I was making, and this is my fear. Your ideas are great but I am not sure the Conservatives have a clue of what they are up against.

Sorry if you have covered this elsewhere and I simply haven't seen it.