Radical candour for Ed Miliband

The climate is changing and we should take that seriously. But climate policy is leading us to ruin, often on unscientific foundations: the now implausible high emissions scenario RCP8.5.

This week, Ed Miliband made a statement to Parliament titled “State of Climate and Nature”:

On the day that the Met Office publishes its “State of the UK Climate” report for 2024, the Environment Secretary and I want to share with the British people what we know about the scale of the crisis and explain the actions that we are taking in response. We intend this to become an annual statement to Parliament.

Let me start by setting out what we know from the science. According to the World Meteorological Organisation, the past decade has seen the 10 warmest years on record globally. It says that long-term global warming, assessed by a range of methods, is estimated to be between 1.34°C and 1.41°C above pre-industrial levels, and last year was the first time we saw an individual year above 1.5°C.

Given my work to expose the cost of Net Zero, I thought I ought to write about science and climate policy: we should take climate change and the response to it seriously as we fight for a free future. Climate change is no excuse for surrendering the principles of a free society.

Members of the public have sometimes asked me to deny that human emissions of carbon dioxide are contributing to our changing climate. That would be unscientific and I won’t do it. We need an honest debate about climate change and the response to it if we are choose the best way to promote human prosperity through freedom.

This article deals with the science and the foundations of public policy, particularly criticising the bridge between them: the commonly-used but outdated and unscientific emissions scenario RCP8.5 which is making the climate debate apocalyptic quite wrongly.

Science and politics

As we saw during the pandemic, science and politics mix poorly. It is an old problem, as this 1950 article makes clear: Science and Politics in the Twentieth Century by James B Conant.

Science and Politics Have Become Deeply Intertwined: In the twentieth century, science and politics – once largely separate spheres – became inseparable, especially in democratic nations facing decisions about national defence and technology. Political leaders routinely face questions requiring technical and scientific expertise but there is no reliable process for resolving conflicting expert opinions. The challenge is especially acute when allocating public funds and evaluating complex technological projects.

Decision-Making in Science Policy Is Problematic: Elected officials must make final decisions on scientific and technical matters but often lack the means to adjudicate between opposing expert opinions. The current system does not satisfactorily resolve disputes among scientists or engineers; technical conflicts can remain stubbornly unresolved at the highest levels of government. There is a pressing need for better procedures to assess and document technical judgments, potentially suggesting a model akin to a judicial process, where expert "hearings" and transparent records help clarify decisions.

Contrasts Between Authoritarian and Democratic Approaches: In authoritarian systems, such as the Soviet Union, science was directly subjugated to prevailing political doctrine (e.g., dialectical materialism) and enforced ideological conformity. Scientific freedom is inherently limited in such environments, with research and theory required to fit party orthodoxy; dissent is suppressed, and political considerations often determine “scientific truth.” In contrast, democratic societies see more diversity and debate, but struggle with integrating scientific advice into policy without falling prey to political pressures or impasses.

The Nature of Science and Its Methods: The article debunks the idea of a single “scientific method,” emphasising instead that science is a dynamic, conceptual process – an “interconnecting group of concepts and conceptual schemes arising out of experiment and observation, and fruitful of new experiments and observations.” There’s a crucial difference between trial-and-error, applied science (improving practical arts using theory), and pure science (extending knowledge without immediate practical goals). Science thrives on a blend of theory, imagination, empirical verification and conceptual development – not merely the mechanistic application of hypotheses.

The Role and Limits of Science in Social Policy: While scientific advances have transformed industry and defence, breakthroughs in the natural sciences occurred slowly and unpredictably – expectations for immediate, profound progress in social sciences or a “scientific revolution” in politics1 should be tempered. Nevertheless, gradual improvements and innovation – drawing on both scientific and historical wisdom – can and should be applied to public policy and organisational design. The “scientific method” alone is unlikely to resolve complex social or political dilemmas; empiricism and common sense, accumulated practical wisdom, and trial-and-error remain essential tools.

Recommendations and Outlook: Society should continue experimenting with new mechanisms for decision-making in science policy, informed by past experience, analogy, and open debate. Good governance requires openness to technical expertise, but also skepticism of experts’ biases and the acknowledgment that even technical decisions are shaped by politics. Ultimately, the separation between science and politics has faded, demanding that nations evolve new methods for balancing expertise, authority, and democratic control in an age dominated by applied science.

With all this in mind. I made suggestions for reform during the pandemic, working with Prof Roger Koppl in particular on expert failure and how to mitigate it. I will return to that work in a later article.

In the meantime, this article focusses on what is and is not certain, how the climate debate has become hysterical and what we can do about it.

There is no doubt in my mind that science and politics mix exceptionally poorly: the purported threat of mass extinction can be used to manufacture hysterical support for daft policies and candidates. Having had enough of this nonsense, I launched the Net Zero Scrutiny Group and supported Net Zero Watch, together with Lord Craig Mackinlay.

We received a great deal of criticism but now, once again, it is increasingly plain we were right: Net Zero policy is wildly off the rails. The centre right political parties have now adopted my position of scepticism about radical interventionist energy policy with huge subsidies.

I would advise politicians and activists to avoid talking about things they don’t understand2, but climate policy is now so important, everyone seeking to wield or influence power ought to know the terms of debate.

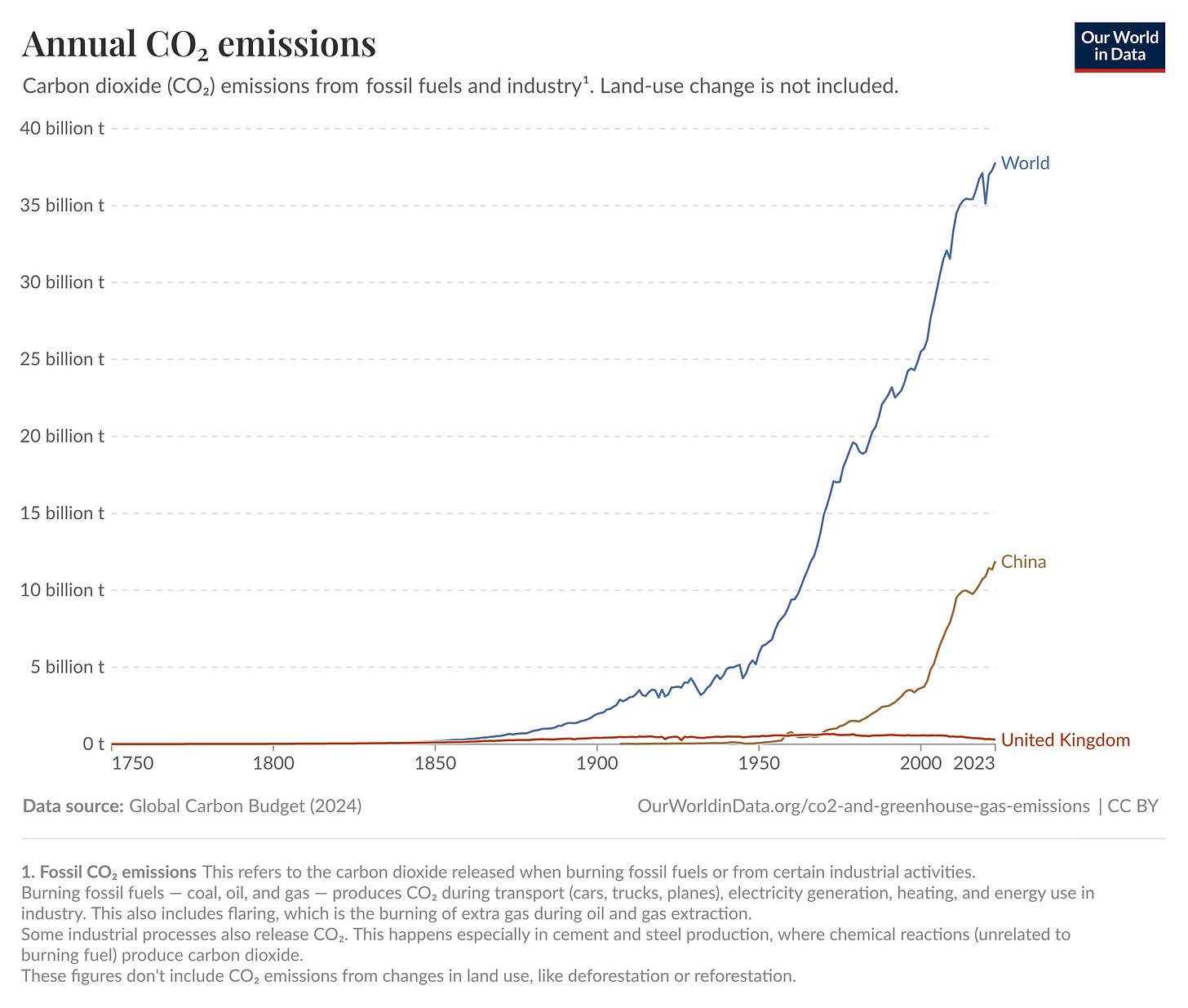

If you would like to compare UK emissions to China’s and others, you can do so through Our World in Data.